Carrying out scientific experiments in the coldest part of the world is tough — even tougher if you’re miles away from Scott Base in a shipping container. But one NIWA scientist insists it’s a lot of fun.

If Craig Stevens wanted to commute from Scott Base to his temporary workplace 25km away, it would take 90 minutes one way by skidoo. When the weather is bad at Antarctica, he and his team couldn’t get there at all. So they camp out.

“It’s much more efficient to have a field camp – we have occasional visitors but otherwise you make the best of it.”

Researching sea ice

Dr Stevens, a NIWA marine physicist, spent two weeks on the ice towards the end of the year with three others – supported by another three at Scott Base - undertaking a series of experiments researching why sea ice is growing in the Antarctic but receding in the Arctic.

Despite temperatures with wind-chill below -30°C outside, Dr Stevens insists his working conditions are comfortable, warm and protected from the wind.

“There are challenges around the weather and getting the camp set up but once it’s in place, the weather doesn’t really matter.

“The only problem is that you can’t go anywhere. You tend not to leave a 100m radius from camp in case the weather changes. Although that’s in part because you are so busy.”

Shipping container campsite

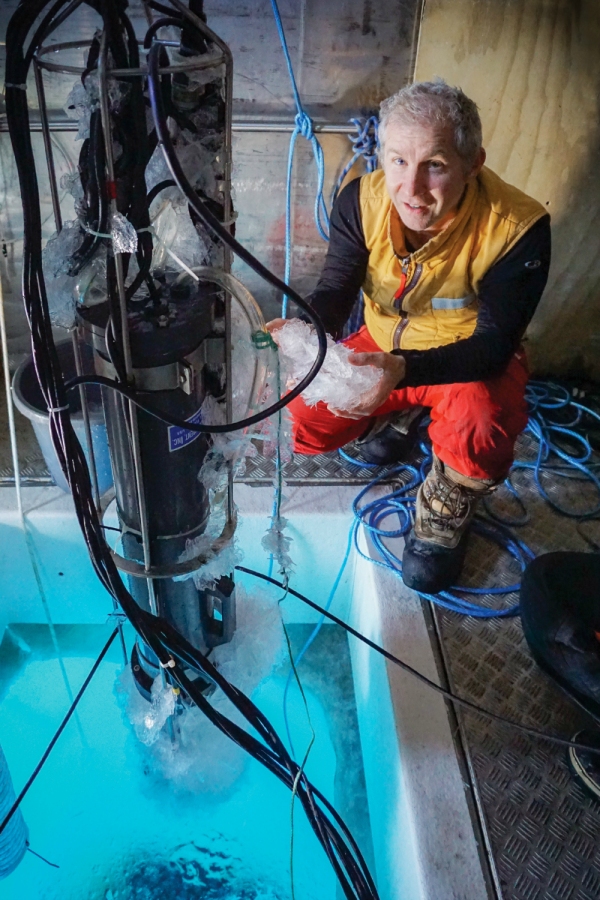

The campsite comprises eight shipping containers – two with holes drilled through the bottom to enable the scientists to access the ocean below for their experiments.

One container operates as a kitchen, another has bunks, one is for cold storage, one houses a generator and the others operate as laboratories.

“It’s very, very comfortable undertaking oceanography here compared to being on a ship that rocks around.

“I tend to like doing the cooking as I can keep in touch with all the various activites, although we share it around a bit once everyone has worked out my recipes all involve hash browns. We take a breadmaker and an oven and we make pizza and cookies. You get sent out with basic field food boxes, which these days is pretty good, and you make the best of it. It’s the fresh fruit that we really miss. Occasionally visitors might bring out mandarins or apples which are always welcome.”

“We have a satellite phone but it rarely gets used. And we choose not to worry about an internet connection – in today’s modern world that is really quite nice. In fact the isolation is part of what makes it so good; you’re with a team, it’s a little bit old-fashioned but really great.”

Never-ending daylight

The days are long though, partly due to the never-ending daylight and partly because time is limited and there is much to do.

The ice below the camp was two metres thick. And beneath this ice lies a similar thickness layer of slushy ice crystals. After drilling through the ice to reach the water beneath, team members had to constantly scoop out the slurry to keep the hole open – while keeping an eye out for curious seals popping up for a visit.

The hole was drilled large enough to fit various scientific instruments which are lowered into the water.

Using a Supercoolometer

One of these instruments is the Supercoolometer, which measures “supercool” seawater formed under ice shelves when “warm” sea water melts the ice underside

“This melted water is very cold and a little fresher than normal seawater. As a consequence it drains upwards until reaches the edge of the shelf. As it rises the reduction in pressure means that the freezing temperature rises and so it finds itself colder than the temperature at which should form ice,” Dr Stevens says.

At -1.9°C, this water is highly significant from a climate perspective and in determining why sea ice, a vital part of climate modelling, is growing in the Antarctic but receding in the Arctic.

“We are looking at the possibility that the answer lies in the production of this supercool seawater. Because it is so cold, the ice shelf water influences sea ice growth far beyond the shelves that make up 40 per cent of the Antarctic coastline.

“It’s also about waving the flag for some of the unique processes of the Earth’s systems and which of those are important.”

Slight changes make a big difference

Dr Stevens says while this water is only slightly colder than freezing, that tiny temperature change is huge in what it means physically because ice starts to form and ocean changes its state.

The suite of instruments measure a range of important quantities from temperature and salinity through to ocean currents and turbulence. The process comes with its own set of challenges with the water freezing on the measuring instruments within an hour of being deployed. This is where the Supercoolometer comes in.

“Part of what we are doing is developing techniques to get around that. You can make measurements but they might be corrupted so this is part of the scientific process to try and evaluate how reliable the measurements are.”

Analysis is underway

Analysis of this latest field trip to Antarctic is under-way and in 2016 the team will measure the ocean behaviour in the ocean cavity beneath the Ross Ice Shelf. This volume of sea water is roughly the volume of the North Sea and barely known.

“Next we’re going to the middle of the Ross Ice Shelf. This time we went through five metres of ice and platelets – in a year’s time we go through 350m of ice. We get to sample a whole hidden ocean that’s essentially never been sampled before - which is pretty exciting.”