It’s been three years in the testing and NIWA scientists now have an analytical instrument that can provide near real-time water quality test results. In addition to other benefits, this means a far quicker answer to the question “is it safe to swim?”.

Recreational water quality is assessed using a combination of variables, with the key one for freshwater being Escherichia coli (E. coli), a bacterium found in human and animal faecal matter. E. coli is used as a microbiological water quality indicator of the suitability of rivers and lakes for swimming and other recreational pursuits.

The traditional test for E. coli requires culturing water samples in a laboratory for at least 24 hours, which can cause delays of up to two days after sampling before the water can be deemed suitable or unsuitable for swimming.

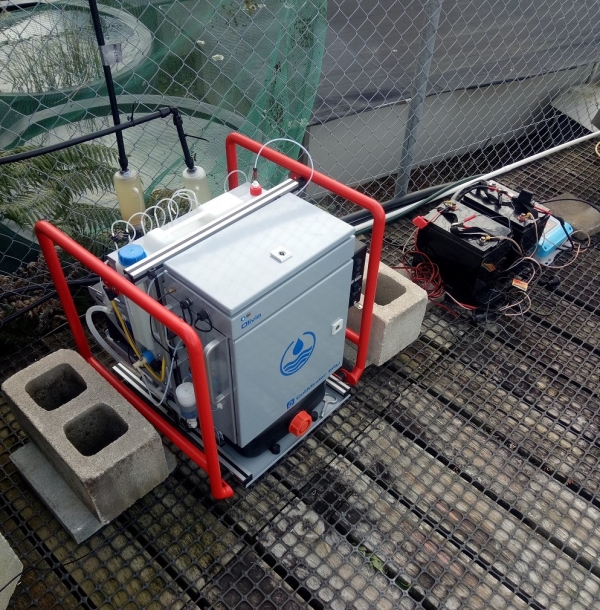

Enter the ColiMinder®, a portable instrument that provides reliable estimates of E. coli concentrations within 30 minutes. It can carry out automated sampling and analysis of up to 50 samples per day. It can also report the results via the internet to further reduce reporting delays, and technicians can adjust the instrument remotely online.

“Until recently, at best we’ve been able to say, ‘the water was safe or unsafe for swimming yesterday’,” says NIWA microbiologist Dr Rebecca Stott. “This doesn’t help people decide where they might go today, or what recreational activities they may safely undertake in the water once they get there. We brought the ColiMinder to New Zealand because it can provide fully automated, rapid microbiological measurements, which can in turn improve public health protection, and our testing has borne that out.”

Since importing the ColiMinder from Vienna Water Monitoring Solutions in Austria in late 2016, Dr Stott and colleagues have been trialling the mobile laboratory in different environments and different seasons, testing and calibrating it for New Zealand conditions. Several of these tests have involved staff from regional councils and other organisations concerned with public health protection.

Trial locations have included a popular swimming spot on the Waikato River, a coastal recreational site in a Hawke’s Bay estuary, an urban stream in Porirua, and a rural site on the Piako River in Waikato. Dr Stott says test results provided important insights into the variability of microbial water quality that would have been missed with low frequency or ‘spot’ sampling.

The testing has confirmed that the ColiMinder can be used to assess saline water as well as freshwater.

“Traditionally it’s difficult to get measurements for estuarine environments where saline water meets freshwater because of the need to do dilutions or effective rinsing of membrane filters to remove salt interference. But through our testing in Hawke’s Bay we now have protocols that can cope with fluctuating salinity for both E. coli and enterococci (the preferred indicator bacteria for marine waters and saline areas of estuaries).

Dr Stott says combining the results from the ColiMinder with results from other in-situ high-frequency water quality monitoring sensors has the potential to pinpoint the influence of individual sources (streams, stormwater drains, and leaking infrastructure) on water quality, as well as indicating where and when health risks arising from faecal contamination of water are likely to be unacceptable.

“We’re keen to hear from water manager at councils and other organisations to investigate how high frequency monitoring could benefit their work to improve the suitability of rivers, lakes and coastal waters for recreation and mahinga kai.”

A smaller, portable ColiMinder machine is also available, which can be used to test microbial health risks in remote locations, or as part of a response to an emergency situation such as a failure in a reticulated wastewater system that has caused discharge of raw or partially treated sewage to a stream, lake or estuary.

Future areas of investigation include refining protocols for online monitoring of common bacteria in drinking water systems, to add an early warning system to raw water intake and treatment process monitoring.

Dr Stott’s latest research has been published in the journal Science of the Total Environment: Cazals et al, “Near real-time notification of water quality impairments in recreational freshwaters using rapid online detection of β-D-glucuronidase activity as a surrogate for Escherichia coli monitoring”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137303

For more information about working with the ColiMinder, contact Dr Rebecca Stott.