Changes to water flow regimes can affect fish in several ways.

Water abstraction or diversion from a stream reduces water velocities and levels, affecting fish habitat. In summer, a shallow flow can promote weed growth, which reduces fish habitat, decreasing oxygen levels at night and increasing pH (i.e. alkalinity) during the day.

Conversely, land use changes from native forest to pasture or to concrete, bitumen and buildings increases the runoff from heavy rainfall, resulting in flash flood flows and damage to streams. Flash floods also increase the probability of fish being washed out of a stream.

The setting of an appropriate flow regime for a given stream is carried out by regional councils. They use fish habitat modelling techniques, developed by NIWA, to ensure water abstraction does not reduce fish habitat.

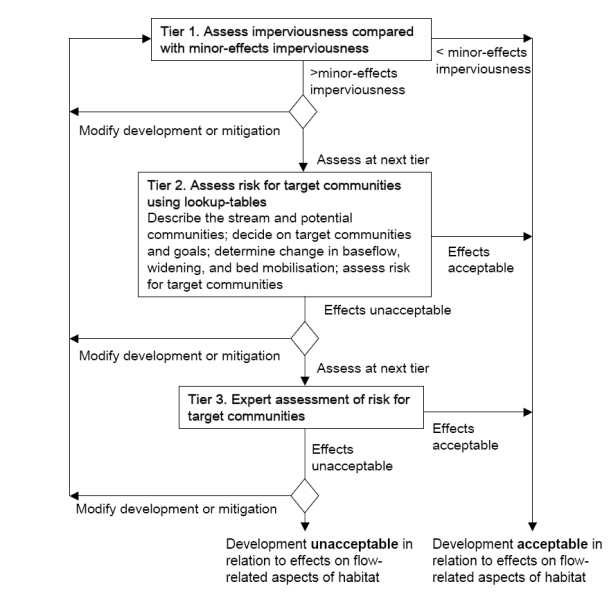

Determination of flow regimes for protection of in-river values in New Zealand

NIWA guide to assessing effects of urbanisation on flow-related stream habitat

NIWA guide to instream habitat survey methods and analysis

What to do:

Establish that a minimum flow has been set for your stream. If you think low flows caused by upstream abstractions are limiting fish, check that the regional council has carried out a proper assessment of the minimum flow and is monitoring all abstractions to ensure that its conditions on consents are being complied with.

Setting a minimum flow does not always allow for natural flow variation. Fish use seasonal flow variations to begin spawning and feeding migrations. Small floods are important for flushing organic debris and silt downstream, and for unclogging the habitats of invertebrates that are key foods for native fish. Therefore, setting minimum flows needs to be accompanied by rules that maintain a near-natural seasonal range of variation in flow, and that ensure floods large enough to restore substrates will continue.

If your stream is affected by flash flood flows from fast rainfall runoff, restoration can involve several approaches. Tree-planting in the catchment is a long-term approach, but where this is not possible, plant grass swales and small wetlands to absorb water runoff before it enters streams. Planting riparian margins on stream banks may also help reduce water runoff and siltation. Rainfall runoff from rooves normally flows straight into drains and into the nearest stream, but some may be diverted into swales or stored in tanks for later slow release to gardens. In high-density housing areas, detention ponds may be required along with the construction of instream structures to deflect high water velocities.